America has always been about reinvention. Disruption from the Industrial Revolution and global competition (sound familiar?) strained Vermont agriculture at the end of the 19th century. In an effort to modernize agriculture, agricultural big thinkers, often funded by wealthy philanthropists, encouraged the development of model farms. From the Vanderbilts’ Shelburne Farms on Lake Champlain to the Billings/Rockefeller Farm in Woodstock, these beautifully constructed agricultural experiments were designed to showcase innovative agricultural practices and labor-saving building designs. Other examples are Brook Farm in Cavendish, Mountain View Stock Farm in Benson, Rockledge Farm in Swanton and the Owen Moon Farm in South Woodstock.

Not surprisingly, the locals, both in admiration and skepticism, saw them as “Gentleman’s Farms” and the name stuck. The sponsors of these lovely experiments saw an opportunity to combine philanthropy with relaxation and the combination of seasonal residence and the model farm was born.

Brook Farm Vineyards is a good example of the evolution of the model farm in the late 1800s. James H. Bates was a local Vermont boy, born at Brook Farm in 1826. Out of economic necessity his family moved out of state and over fifty years later he returned as a “gentleman farmer”. He had made his fortune in the advertising business, and came back to develop his birthplace into one of Vermont’s finest examples of a model farm still in private hands. The farm reflects the culmination of agricultural development based on animal power and diversified farming with its grand summer mansion, nine supporting buildings and surrounding landscape.

To read the remarkable story of how this 200-year-old farm was again coolly reinvented for the 21st century, click here.

For the first 11 years of his life, Bates lived on Brook Farm until his father was “infected with the western fever” and moved the family to Kalamazoo, Michigan. As Bates came of age, the agricultural base of the country’s economy had begun to wane and 11 million Americans left the farm for the city in search of better opportunities. Bates became part of this migration, which E. Lakin captured in his Autobiographical Notes:

It was in the destinies that James Hale [Bates] should grow up a farmer boy, scholarly amd [sic] book-loving…. and after some years of rather fruitless endeavor in this Western land, go to seek his fortune in the East and find it there. He has long been known as an intelligent, wealthy and honored gentleman, living in fine style in Brooklyn and doing business—an advertising agency—in the City of New York.

His story would sound very familiar, over a century later. From his perch as a disruptor, in bustling Brooklyn, behind his desk at an ad agency, it is easy to see how Bates might have been drawn back to the hills of Vermont.

He moved back, part of a trickle of seasonal visitors that grew to a flood. The state was undergoing a profound shift as subsistence farms depopulated, and seasonal residents, intrigued by the opportunity to help the local communities, invested in the improvement of local agriculture. Sound familiar?

By the late 1800s, an estimated 176,000 Vermonters had left the state. Vermont responded to the depopulation with initiatives to encourage the redevelopment of existing farms by seasonal residents. One of its target groups was the Vermont ex-pats. Towns threw events like “Old Home” days with activities to entice affluent family members, such as Bates, to return home and bring their money and brains with them. After 1850, railroads made it easier for urban families to trade the heat and congestion of the city for the beauty of Vermont.

Bates returned to Brook Farm at 55 years old and set about building a grand residence along with the model farm, where his family retreated from the Brooklyn heat from June through October. We imagine that not only were they agricultural exemplars, but patrons of the local arts and culture in the surrounding communities. Clearly the house was built for parties, with soaring principal rooms to host glittering gatherings of locals and summer folk alike.

Below is a tour of the historic buildings at Brook Farm, which are largely unchanged since the late 19th century when James H. Bates and his family spent their summer holidays in residence.

Bates Mansion

Built as a summer home in 1894 on the site of Brook Farm’s original main house, this magnificent Georgian Revival style country mansion rests on a rough-cut-stone foundation. Stylistically eclectic, the design draws on Georgian, Dutch Colonial and Adamesque references. The main entrance follows a Palladian motif. The upper section of the nine-foot high “Dutch door” is glazed with diagonally-crossed muntins topped with an arched fanlight. Above the side windows are fixed sashes with muntins radiating to an ellipse. The mansion overlooks the Twenty Mile Stream valley extending to the south between forested hills, with fields, pastures and orchards lining the road, bounded by stone walls, wire fences and treelines.

Carriage Barn

Located just uphill to the west of Bates Mansion, this long Gothic-style two-story wooden clapboarded barn probably dates from the mid-1880s. It runs east and west, forming the south side of the yard around which the majority of the farm buildings cluster. The first floor of the barn’s interior is divided into quarters with rows of enclosed horse stalls. Tongue-and-groove softwood paneling sheaths the walls. The west half of the second floor is used for hay storage, while the eastern half was finished into small rooms to provide living quarters for hired help.

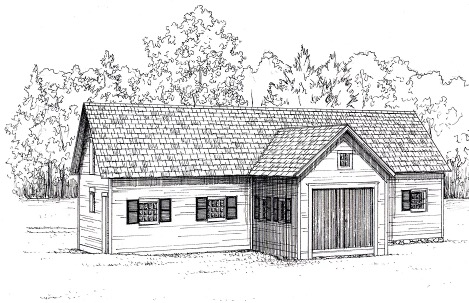

Tractor Barn

Located between the three barns, the equipment shed consists of two wooden clapboarded one-and-a-half story sheds facing east with a small ell extending from the rear northwest corner. The center section is the oldest. A photo taken before 1894 suggests that it was a woodshed wing on the west side of the original farmhouse, and presumably was moved to its present site when Bates Mansion was constructed in 1894.

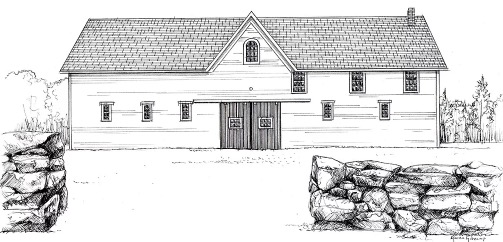

Cow Barn

The largest of the outbuildings on Brook Farm, the Cow Barn faces south, defining the northern edge of the farmyard with the land sloping steeply away to the brook behind. Built for James Bates after 1881 to house the farm’s expanding dairy herd, the Cow Barn is an enlarged version of the earlier “English” barn design with side doorways providing an off-centered drive-through. On the interior, the first floor of the Cow Barn is divided into three areas with the center providing the drive-through and equipment storage area. A square two-story enclosed silo was added to the west of the rear door. Stalls for the farm’s work horses were later converted to box stalls for horses, calves and small animals on the west.

Pig Shed and Blacksmith Shop

This T-shaped one-and-a-half story gable-roofed building, located between the Cow Barn and the Caretaker’s House, was probably built in the 1880s, being finished in a similar style to the Caretaker’s House, Creamery and Chicken Coop. The south wing also was used as a blacksmith shop. Photos taken around 1900 and the 1930s show two small gable-roofed cupolas with louvers to provide ventilation. The Pig Shed is remarkably similar to a design illustrated in the American Agriculturalist and published in the 1881 Barn Plans and Outbuildings.

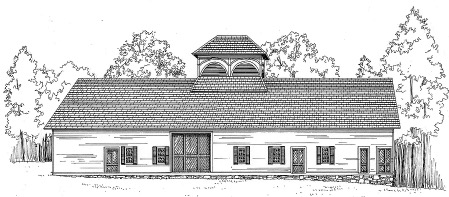

Chicken Coop

Caretaker’s House

The Creamery

Located just southwest of the Caretaker’s House, the Creamery is of a similar style and probably also dates from 1880s, although some components, like the window sash, may have been recycled from earlier buildings. The first story is divided into three full-width rooms.

Garden Shed/Greenhouse

Located on the southeast corner of the garden plot, which is south of the Carriage Barn, the Garden Shed is a small single-story wooden building, sheathed with clapboards and topped by a steep hipped roof with an entry door on the north side. The Garden Shed and Greenhouse appear to date from the early 1910s.

Brook Farm is ready for its next stewards and is for sale.