Editor’s Note: Below is the remarkable story of a 200-year-old Vermont farm and its many incarnations. The place has transitioned from a subsistence hill farm to a model agricultural estate to today’s ultra-boutique vineyard with its grand summer mansion and original outbuildings, coolly reinvented for the 21st century.

The History of Brook Farm

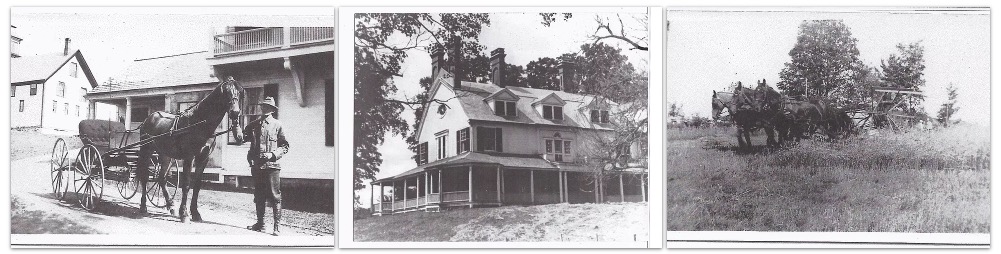

Reaching its zenith as a model gentleman’s farm in the mid-1890s, Brook Farm survives as a remarkably intact example of a country estate with a grand summer mansion built on the site of an existing working farm. The Bates Mansion itself is an outstanding example of the Georgian Revival style of architecture with especially fine workmanship and sophisticated details. With over a dozen supporting buildings ranging from a variety of barns to a house for the hired help, Brook Farm is a significant example of a group of buildings and surrounding landscape that reflects the culmination of agricultural development based on animal power and diversified farming in the late 19th century.

One of the larger farms in the town of Cavendish, Vermont, the original settlement dates from 1788 when Nathan Conant purchased 78 acres of easterly-sloping land from Timothy Hildreth, who was one of the first landowners of the town. Conant constructed a hipped-roof two-story house with a center chimney. (Moved around 1894 from its original site to a site just east of the Caretaker’s House to allow construction of Bates Mansion, and subsequently moved away from the farm site, the original house is said to have been reconstructed on Greenen Road in the village of Proctorsville, Vermont.)

During the 19th century, a wing and small barn or woodshed were connected to the original house, and a larger barn was built for hay storage and to shelter farm animals. In 1820, the farm was mortgaged to William Jarvis of Weathersfield, Vermont, who, a decade earlier, while United States Consul to Lisbon, had imported the first large number of Merino sheep to America, marking the beginning of the “sheep boom” which brought an era of prosperity to many farmers in Vermont and New England.

By the mid-19th century, the farm had been sold to Chivey Chase, who increased its size to 185 acres. Agricultural census figures show that, like many Vermont farmers, Chase decreased wool production, while increasing dairy production, as the profitability of raising sheep for wool declined with the opening of the west and increasing competition from Australian herders.

By 1860, the Chase family produced for their own use and cash income about 600 pounds of butter and 300 pounds of cheese annually from a herd of five milk cows, as well as 200 pounds of maples sugar and 200 bushels of potatoes. In addition, a variety of crops, including hay, buckwheat, corn, beans, oats and apples were grown, primarily to provide food for the family, the pair of workhorses, a pig and a sheep. By 1870, however, cheese production on the farm had stopped, with milk presumably being shipped directly to a centralized cheese factory, the closest being the Eagle Cheese Company in Proctorsville, Vermont. Ten years later, the dairy herd had been increased to 15 milk cows. Liquid milk had become a major source of income, with 4,300 gallons produced. Maple sugar production also increased to 600 pounds a year.

Chivey Chase died in 1878, and in 1881 his heirs sold the farm to James H. Bates, a cousin of the Chases who was born on the farm, but had become a successful businessman in Kalamazoo, Michigan and Brooklyn, New York. James Bates developed the farm, increasing its acreage substantially by purchasing adjacent farms and woodlots. He constructed numerous outbuildings, including the Carriage Barn for the carriage horses and with living quarters for hired help, a Cow Barn for the herd of about 30 Jersey cows, a Pig Shed, a Chicken Coop, a Caretaker’s House, a Creamery in which butter was produced, a Sugar House for making maple sugar, and several other buildings no longer standing, including an Ice House located between the Pig Shed and the Old Barn.

These detached wooden clapboarded outbuildings, all built in a similar vernacular style, each serve a specific agricultural purpose. The Cow Barn is particularly notable, combining the traditional “Yankee Barn” design (with a center drive-through, horse stalls on one side and cow stations on the other and hay lofts above) but built on a much larger scale. The internal square wooden silo reflects the shift from feeding cattle hay to chopped fodder during the winter. The Chicken Coop and the Pig Shed follow innovative agricultural building designs published in the early 1880s in such journals as the American Agriculturalist. For example, the T-shaped Pig Shed with the ell used for slaughtering and feed preparation, and individual compartment opening through low doors to separate pig pens in the rear. Large sliding multi-pane windows on the south and east sides of the chicken coops also were recommended in agricultural publications in the mid-1880s.

The Rise of the Gentleman’s Farm in Vermont in the late 1800s: click here to read more.

For several decades, James Bates and his family lived at Brook Farm from June through October, returning to their home in Brooklyn, New York, in the winter, although Charles Chase continued to serve as the farm manager and lived with his family in the Caretaker’s House throughout the year. While this arrangement of seasonal occupancy by an owner with full-time hired help was uncommon in Vermont before the Civil War, it does reflect changes during the last quarter of the 19th century, when a rapidly expanding national economy produced wide differences in disposable income, as the profitability of farming declined relative to the fortunes that could be made through business. The option of routinely traveling the several hundred miles between the metropolitan areas and the Vermont countryside became a possibility as an efficient passenger transportation system reduced travel time from days to hours.

Bates Mansion was constructed in 1894. In one of several articles published in the local newspaper commenting on the project, the June 8, 1894 Vermont Tribune, of Ludlow, Vermont, reports, “Work on the new summer residence being built for the Hon. J. H. Bates is being rapidly carried forward. A large fore of men are employed who are under the supervision of contractor Ross of Middlebury (Vermont)…” Indeed, the construction of the mansion provided needed jobs at a time when at least one major local woolen factory had closed down during a period of widespread economic decline.

Although the architect is unknown, the design of the mansion borrows elements freely from the Georgian, Adamesque and Federal styles, but magnifies their scale and proportions in the Georgian Revival style.

The interior finish in the main portion is especially outstanding with over-scaled doors, richly embellished fireplaces, and a large two-story entry hall featuring an elliptical balcony opening and a grand corner staircase.

Equipped with 1890s conveniences, the house was illuminated by chandeliers and wall sconces fueled by acetylene gas generated in the basement. A speaking tube connected the master bedroom with the kitchen. Gravity-fed water from a spring located on the hill east of Twenty Mile Stream Road plumbed the kitchen and bathrooms. Overall, the Bates Mansion is one of the finest Georgian Revival seasonal farm houses in the state, and many of its interior details survive intact.

The large walls of cut stone which bound the fields to the south of the farm buildings and along Twenty Mile Stream Road, and the cylindrical stone piers marking the driveway entrance, reflect an effort to create an enduring picturesque landscape. The stone walls enclosed an orchard and garden for vegetables, fruit and flowers southwest of the mansion. Probably built after 1900, the Garden House and Green House made it possible to grow plants requiring a longer frost-free season.

After James Bates passed away in the late 1920s, the mansion and twenty acres was willed to his wife, and the remaining acreage to his cousin, Charles Chase, the caretaker. Most of the farm was subsequently purchased by Louis Schmidt in the early 1930s. A hand-drawn map owned by Stewart Schmidt, probably of around 1936, shows the farm surrounded by cultivated fields growing such crops as corn, oats, clover and hay.

Louis Schmidt became the new owner of Brook Farm in the 1930s and raised racehorses. His son Stewart Schmidt owned Brook Farm from 1961 to 1986 with his mother, Marian Schmidt, and his sister, Karen Stewart. Schmidt occupied the north wing of the Bates Mansion with his wife Jackie, son Bruce and daughter Lisa as their primary residence. The main section of the mansion was regularly and continuously rented to nine families during the winter ski season. During the summer, the main part of the mansion was available for rental but was not aggressively marketed.

George and Diana Davis took ownership of Brook Farm in 1986. They were responsible for establishing the farm on the National Register of Historic Places. The Davises operated Brook Farm as a destination wedding business.

Doug and Jennifer McBride became the owners of Brook Farm in 2008. Doug, a New York City attorney and business owner, and Jennifer, founder and owner of a couture textile design business, undertook a comprehensive search for a suitable property and chose Brook Farm because they were entranced by its aesthetics, its potential and as a place to raise their family. They planted four acres of vines, specializing in cold hardy varietals, complete with a tasting room and winery. Using New World grape-growing practices, they produced small-lot, handcrafted bottles of exceptional wines that are balanced, harmonious, and complex.

Today the distinguished mansion, the cluster of farm buildings and picturesque stone walls and agricultural landscape of Brook Farm survive as a notable example of architecture and land use which reflect the culmination of animal-powered agricultural development in the late 19th century, when an older Vermont hill-farm was transformed into a model estate farm, expanded and subsidized by a seasonal owner.

The farm is currently for sale and waiting for the next steward of the estate. To learn more about Brook Farm Vineyards as one of the finest examples of a model farm, click here.